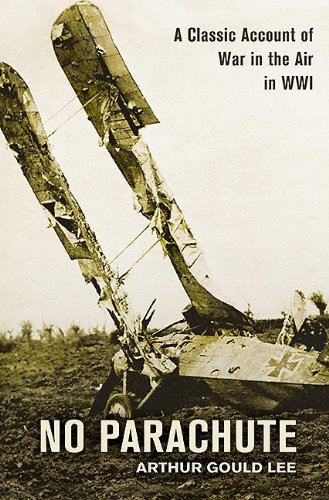

Arthur Gould Lee, No Parachute

Appendix C, Why No Parachutes?

Product Details

- Hardcover: 233 pages

- Publisher: Time Life Education (June 1991)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 0809496127

- ISBN-13: 978-0809496129

- Product Dimensions: 8.4 x 5.6 x 1 inches

- Shipping Weight: 1.1 pounds

- Average Customer Review: 4.8 out of 5 stars (9 customer reviews)

- Price: $48.80 plus shipping (<-- What I paid for out-of-print hardcover. Currently, Amazon sells the Kindle edition for $9.99.)

1. Short review:  (Amazon rating: 5 out of 5 stars -- I love it.)

(Amazon rating: 5 out of 5 stars -- I love it.)

I love the body of the book. The appendices -- each and every one -- I find fault with.

(Amazon rating: 5 out of 5 stars -- I love it.)

(Amazon rating: 5 out of 5 stars -- I love it.)I love the body of the book. The appendices -- each and every one -- I find fault with.

2. Long review:

2.1. What I liked: See my first review.2.2. What I did not like: See my first review.

2.3. Who I think is the audience: Air combat buffs. History buffs.

2.4. Is the book appropriate for children to read? Yes. No worries.

2.5. On the basis of reading this book, will I buy the author's next book? Yes. Now have Open Cockpit.

2.6. Appendix C. Why No Parachutes?

Nothing more mystified the pilots and observers of the R.F.C., R.N.A.S., and R.A.F. during 1917-1918 than the dour refusal of their High Command to provide them with parachutes. During the half-century that has followed, no question has more puzzled air historians on every level.

Because no specific reason was ever established for their refusal, a convention has grown up over the years, erected on the gossip and half-truths of the day, that the decision against parachutes was taken first because no reliable parachute then existed, and second because so convenient a facility for escape might invite pilots to abandon their aircraft without a determined fight.

The first reason was unquestionably given by those responsible, but it was untrue. The second was a slur on the flyers who daily risked their lives in France, and one which has since provoked indignation among the survivors of those who were there. But it is an invention. That some such notion was in the air as a rumour is not to be denied, but it was not based on an official attitude.

I have made a close examination of all the War Office files dealing with parachutes during 1914-1918, files not previously open for inspection except under ban of official censorship, and nowhere have I found any specific statement by any officer on which could be pinned the calumny that parachutes would encourage unnecessary abandonment of aircraft.

Another convention that has emerged in recent years is the habit of attribution the official denial of parachutes to one man, and one man alone, General Trenchard. This trend is based partly on a passage in his biography, by Andrew Boyle, which states that Trenchard's attitude to parachutes 'was characteristically spartan. His balloon observers, being defenceless, were issued with them, but not his airmen.'

This statement is too vague to hold the significance placed on it. In the early and middle stages of the war Trenchard was not the dominating figure he afterwards became. Even if he had been emphatically against parachutes he could not have imposed his bias over two years on other R.F.C. officers of similar or higher seniority. Moreover, as Commander in the Field, and later Chief of the Air Staff, he would have been much too occupied with weighty day-to-day problems of high direction to be able to intervene frequently in this one question of technical equipment.

In none of the War Office files mentioned have I found evidence that he was in any way responsible for the denial of parachutes. On the contrary, his name is conspicuously absent from the list of senior R.F.C, R.N.A.S and R.A.F. officers at the War Office and Air Ministry who between them did collectively smother the development of the parachute.

The argument put forward by some of these officers that no reliable parachute existed was merely evidence of ignorance. Parachutes were in regular use before the was at fairs, displays and country shows in Europe and the United States, in exhibition jumps from free balloons, carried out by both men and women, and only rarely with accident.

In these parachutes the weight of the falling jumper pulled the canopy from a container attached to the basket of the balloon and immediately opened it. To attach so bulky a container to the early aeroplanes, fragile and underpowered, occurred to no one until March 1912, when a successful jump from 1,500 feet was made in America. The feat was repeated in England in May 1913, when a pull-off fall was made from 2,000 feet over Hendon aerodrome.

In 1908, in America, a different kind of parachute had been introduced, for free fall, in which the parachute was attached as a pack to the jumper, and opened by him by a ripcord and handle as he fell. This new contrivance was employed only for balloon jumps until October 1912, when a similar pack was used in a free-fall jump from a Wright aeroplane, again in the U.S.A. This dramatic advance, which was repeated at shows and displays through the States, held no significance for any of the supposedly alert minds engaged in developing the infant flying services of both the U.S.A. and the then much more militant nations of Europe.

It is thus indisputable that two years before the war there existed a free-fall pack parachute of proven performance, which though perhaps immature by modern standards, could have been take up by any of the powers and developed alongside the then equally immature aeroplane.

Although, after World War I broke out, observation kite balloons were provided with the traditional showman's type of free-balloon parachute, not only were the 1912 free-fall drops from aeroplanes completely forgotten, but nobody in authority gave a thought to the possibility of adapting the reliable balloon-type parachute for use from aeroplanes.

However, the initiative had already been take by a civilian, Mr E. R. Calthrop, a retired engineer, who had developed a new design of parachute for the simple, altruistic purpose of saving lives. This unconvincing motive, together with the unhappy name he gave to it, 'Guardian Angel', were enough to damn it in the eyes of most service people, but the Guardian Angel, though not a free-fall, and far from perfect by later developments, was a sound, well-thought-out proposition, more compact and quicker in action than the old fashioned Spencer parachutes supplied to kite-balloon observers.

But Calthrop's invention, perhaps because his approach to inflated officialdom was not always sufficiently tactful, was regarded by the War Office and Admiralty with dislike, and every high-level advance on his part for tests and trials was brusquely rebuffed.

War Office files show that even in May 1914, before the war began, Calthrop, whose parachute had already been successfully tried out at Barrow-in-Furness with the co-operation of Vickers, invited the R.F.C. and R.N.A.S. at Farnborough to test it also. Captain E. M. Maitland of the R.F.C., who had done a 7,000-foot parachute jump from an airship the year before, was quite prepared to test it, but there is no evidence that any result followed from this or similar invitations made to both War Office and Admiralty.

Later, in October 1915, at the Royal Aircraft Factory, the enterprising Superintendent, Mervyn O'Gorman, one of the few people alive to the potentiality of the parachute, and with an experienced balloon jumper on his staff, proposed to experiment with a Calthrop. 'I have fitted this to an aeroplane for preliminary trials with a dummy', he wrote to the Directorate of Military Aeronautics, seeking approval for the modest expenditure involved.

'Do you wish experiments of this nature to be proceeded with?' minuted the Assistant Director of M.A. 'No, certainly not!' wrote General Henderson, G.O.C. of the R.F.C. What Daimler's Chief Engineer, A. E. Berriman, called 'some very interesting experiments' were thus abruptly halted. A year later a junior staff officer had the effrontery to suggest that permission might now be given for the experiments to be resumed, but his nose was rubbed in Henderson's 'Certainly not!'

Undeterred, Calthrop persevered in his efforts to gain official approval, but he was up against influences both practical and intangible. That the primitive aeroplane of 1915-1916 could not carry the weight of a parachute without some sacrifice of performance was an objection every pilot understood and accepted though not perhaps to the degree expressed by a gallant R.N.A.S. officer, Commander Boothby, who wrote: 'We don't want to carry additional weight merely to save our lives.'

The intangibles were much less acceptable to the fighting airman. He could not easily tolerate the customary Whitehall opposition to change, to new notions, which existed at high levels in even the young and vigorous R.F.C. and R.N.A.S. Nor did he appreciate the attitude of some senior officers, influenced no doubt by the traditions of the sea, who believed that the occupants of a stricken aeroplane should dive to their deaths with a stiff upper lip, in the manner of the captain of a sinking ship.

A further intangible was the sheer ignorance of those members of the Air Board who lacked experience of air combat except in the carbine era. Even so fine an officer as General R. M. Groves could write: 'Smashed aircraft generally fall with such velocity that there would hardly be time to think about the parachute.' At the time this sentence is written, some 200,000 airmen have saved their lives by parachutes because they managed to find time to think.

Another member of the Air Board, Lord Sydenham, wrote: 'The point is, could pilots make use of the Guardian Angel parachute at the moment when it becomes clear that their machine had come to grief?' Lord Sydenham was not an airman, and his qualifications adjudge on this question were outstanding only in the negative. The sixty-nine-year-old peer's soldiering days had ended ove twenty years earlier, and his two previous public appointments had been Superintendent of the Royal Carriage Factory and Chairman on the Royal Commission on Contagious Diseases.

The Air Board decision on October 1916 was that it should await further developments. But developments by whom? The hoary process of passing the buck was now in operation. In January 1917 the secretary of the Board wrote: 'I gather from General Brancker that there is at present no idea of using parachutes in connection with heavier-than-air craft.' This was thought unnecessary because the R.N.A.S. was now experimenting with parachutes for use in airships.

But at the time that the Board, and the higher officers of the technical directorates, were holding down the Guardian Angel, trials of it were being held by junior officers at Orfordness Experimental Station, where during January successful jumps were made by Captain C. F. Collet from a B.E.2c. No member of the Air Board took any interest in the reports submitted, and not for a full year were the tests resumed at the same station.

But in France General Trenchard heard of the trials, and despite his many preoccupations as Commander in the Field, suggested that they be continued in France. They were not continued anywhere. On January 16th he asked for twenty black Calthrop parachutes for dropping spies from aeroplanes behind the German lines, and the records show that they were delivered to No 2 Aircraft Depot between January and March. Trenchard was at least not blindly opposed to parachutes.

Yet successive members of the Air Board continued to rebuff Calthrop's efforts. In May he made yet another approach, and after referring to the Orfordness trials and the spy-dropping operations, suggested that if his parachutes could not be used by squadrons in France they might at least be employed in training schools. General L. E. O. Charlton's decision in the column of the minute sheet was simply 'No!' Calthrop persisted 'in view of the many deaths from the burning of pilot'. 'Not many', commented Charlton.

Calthrop had heard of the suggestion that possession of a parachute might 'impair a pilot's nerve when in difficulties, so that he would make improper use of his parachute, with the result that more machines would be crashed'. He argued that surely an airman at the Front, knowing he could use his parachute in emergency, 'would attempt to achieve more', but this rational view, which was to be borne out a thousand times in World War II, inspired no reaction.

Among the stock attitudes adopted by members of the Directorate and the Air Board to account for their hostility to parachutes, additional to such notions as that a falling airman would lose consciousness, was the one advanced by the Board's secretary, Major Baird, M.P., in the House of Commons, when he stated that 'pilots did not desire parachutes for aeroplanes'. This view was based on that held by those senior R.F.C. and R.N.A.S. officers who had never experienced fierce lethal air combat, nor witnessed the desperate need of comrades falling to their death in broken or burnine planes. Such as Groves, when he wrote: "The heavier-than-air people all say that they flatly decline a parachute in an aeroplane as a life-saving device worth carrying in its present form'. The people he referred to were not the pilots of B.E.s and R.E.s, or Nieuport and Sopwith two-seaters, or F.E.8s and the other death-traps then being flown in France.

Such statements were evidence of the wide gulf that existed between the fighting ranks of the R.F.C., the pilots and observers in France up to, but not often including, the squadron commander's grade of major, and the ranks who were too senior to fight, and who never experienced post-Fokker air fighting in any form.

The truth was that from early 1917, especially during and after the ' Bloody April' losses, there were few fliers with any experience of air fighting who were not obsessed to some degree, though usually secretly, with the thought of being shot down in flames. The top-scoring British ace Mannock was the classic example. To all these a parachute would have been a stiffener to strain and morale. But their views did not go beyond the level of the squadron or wing commanders, who feared that to support such attitudes would expose them to criticism for tolerating morale-weakening influences.

Another stock attitude was that the Guardian Angel was not efficient enough. Under Government auspices it could have been developed and improved quickly and at trifling cost, and a reliable free-fall parachute would undoubtedly have been evolved within a few months. But the active-service flier did not want to wait for perfection. He wanted something quickly, that would offer a hope of escape, much as a lifebelt offers hope to a seaman from a sinking ship. Even if the parachute were not infallible it would offer a sporting chance, which was better than a death that was certain.

At length, by the end of 1917, a Parachute Committee had been formed on the recommendation of General Maitland, to examine whether or not parachutes should and could be provided. The secretary, Major Orde-Lees, was a keen and experienced parachutist, but not most of those with whom he worked. 'I doubt whether the practicable application of the Guardian Angel parachute is possible during war', wrote the Controller of the Technical Directorate, who then added: 'I think that one parachute should be sufficient to rescue both pilot and observer.'

But in France parachutes at last found support from a high-ranking officer, General Longcroft, commanding the 3rd Brigade, R.F.C., one of the senior officers who was not too senior to fly fighting machines and to make parachute descents. He wrote that 'I and my pilots keenly desired parachutes, and recommend the Calthrop method of fitting the pack to the top of the fuselage'. The official argument against this proposal was that 'it would impose a dangerous strain on the pilot', which was apparently considered worse than being killed. Persisting, Longcroft argued that ehe principal use of the parachute would be to get clear of a burning plane. He added that he had heard the objection that pilots might jump prematurely, but, as a practical parachutist, he did not believe it. His letters went into the pending tray.

By now the French and Italians, and, as was shortly to be shown, the Germans, were all well advanced in experiments in parachutes, and in January 1918 the Air Board was at last driven into giving Calthrop an order, but mainly, as Brigadier-General MacInnes noted later, 'to keep the firm alive'. Subsequently, Calthrop was permitted for the first time to publicise his invention, and he then dislcosed that many flying officers had approached him to supply and fit a parachute at their own expense, but that the Air Board would not countenance any such demonstration of poor morale. After all, Major Baird had officially stated that pilots did not want parachutes.

But ideas were changing, though not to the extent of producing action. 'The question of parachutes now requires more consideration than has been given to it in the past', wrote Commander W. Forbes-Sempill, D/D.A.T.S. in April 1918. 'I think it is no exaggeration to say that everyone agrees that parachutes should be provided on aircraft.'

This view was given a fillip in mid-1918 when the Germans started using free-fall parachutes in France, so provoking a Press and public reaction which Whitehall could not ignore. In September, as a result of tests made in France with S.E.5s and Snipe, a request for 500 Calthrop parachutes was submitted. Except for one minor modification, they were exactly the same as the model standardised in July 1916. But they were never employed in action. The war ended without any parachutes being used by the British in France, except for the dropping of spies.

The War Office files show clearly that for this dereliction, no one man, nor even any specific group of men, can in fairness be indicted. (!!!) It was the collective official mind actuated by intangible prejudice which was responsible. As Calthrop wrote with understandable bitterness in January 1919: 'No one in high quarters had any time to devote to investigating the merits of an appliance whose purpose was so ridiculously irrelevant to war as the saving of life in the air.'

2.7. Critique.

In this, the last appendix, AGL wrote thirty-six paragraphs. I find no fault with the first thirty-five. The last is rubbish.

In the Air Force, I was taught there are three things that come with command: authority, execution (action, if you like), and responsibility. A commander can delegate his authority to a subordinate. A commander can delegate the execution to a subordinate. But even though a commander may hold a subordinate responsible for the use of delegated authority and for execution of a mission, the commander retains full responsibility himself.

The commanding officer always holds full responsibility for his unit. He is responsible for the execution of the mission, the material (aircraft, guns, ammo, tents, victuals, transport, and so forth), and the safety of his men.

The safety of his men. This means that every squadron commander in the Great War was responsible to see to it that his airmen had machines to fly that were as safe as they could be made. That included providing parachutes.

Above the squadron commanders were the wing commanders and, eventually, the General Officer Commanding, R.F.C. They were ultimately responsible for the safety of their airmen.

The R.F.C. had two GOCs: David Henderson and Hugh 'Boom' Trenchard. These two men were and are to blame for the deaths of R.F.C. airmen due to lack of parachutes.

2.8. Links:

Open Cockpit

Fly Past

2.9. Buy the book:

hardback with ugly cover: No Parachute

hardback with misleading cover: No Parachute (used)

paperback with pretty cover: No Parachute (used)

Kindle ebook: No Parachute